By Katie Moritz | Rewire

When James Garrett Jr. was a kid, he would watch the tall buildings in the Lowertown neighborhood of St. Paul, Minnesota, go up. Born in the Carribbean and raised in St. Paul, he would marvel as the cranes worked.

“I would be late for school, sitting there for hours,” he said. “I’d count the floors—have they done any more floors since yesterday?”

He already knew then he wanted to be an architect, to design the buildings that made up his hometown. Decades later, he’s one of three partners at 4RM+ULA (pronounced “formula”), an architecture firm located in the heart of the same place he was so drawn to as a child.

“I kind of feel in a lot of ways Lowertown adopted me,” he said in his sundrenched design studio. “Then I kind of adopted it. It’ll be a sad day when I leave Lowertown.”

A desire to rebuild

4RM+ULA designs everything from city-owned infrastructure to social-minded art installations. In the more than 15 years since Garrett founded the company with partners Nathan Johnson and Erick L. Goodlow, it has grown, filling up its colorful office space in St. Paul and branching to a new location in Manhattan in New York.

Garrett hopes the company will go global. When hurricanes devastated Puerto Rico and Garrett’s home island of St. Thomas last year, Garrett and his wife, also an architect at 4RM+ULA, rushed to provide aid. But they also realized their company could play a part in the rebuild.

“An office down there would give us an ear to that region,” he said.

As for the other islands that weren’t touched by the storm, they’ll need to get ready for the next one, Garrett said. Climatologists predict that climate change will cause more frequent and more ferocious tropical storms.

Professionals can get ahead of a looming crisis, building “in a resilient way that can survive the coming storms.”

Garrett wants to help introduce renewable energy sources to the region as well. New infrastructure should be strong and sustainable.

“We have the technology now that (that level of devastation) should never happen—resiliency models of rebuilding and retooling,” he said.

‘Ask the ancestors’

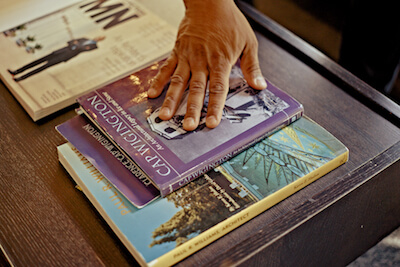

Garrett’s work draws on the history of his family and the place he calls home. The United States’ first black municipal architect, Cap Wigington, was Garrett’s grandfather’s godfather. Sixty of Wigington’s designs still stand in St. Paul today. Garrett’s grandfather was an author who wrote books on St. Paul’s black history.

For Garrett, “there’s kind of a link to being involved in architecture and design.” His father encouraged him to become an architect, a huge driving force in his career.

“My father always believed in me and believed that I was a good decision maker… and that anything I really was interested in that I would find a way to pursue it and make it manifest,” Garrett said.

The last conversation Garrett had with his father before his father passed away was about attending graduate school for architecture. It was Garrett’s dream to own his own firm.

Garrett’s father told him: ” ‘Whatever choice you make, I’m confident it will be the right one. You’ve always made good decisions, you’re going to be fine. I’m 100 percent behind whatever decision you make.’”

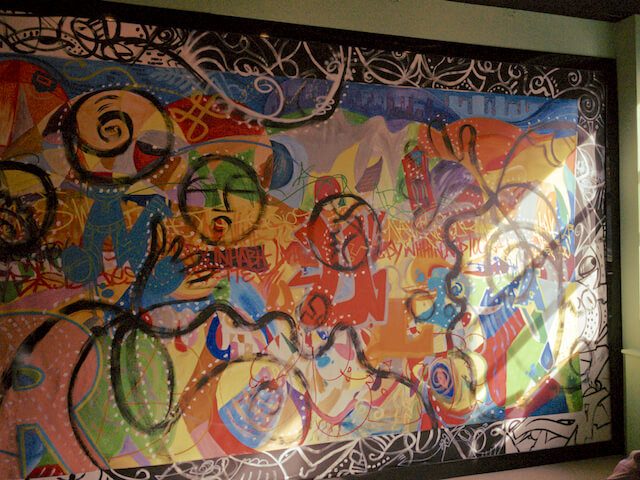

A vibrant and dynamic floor-to-ceiling mural by local artists Ta-coumba Aiken and Roger Cummings that provides the centerpiece for 4RM+ULA’s St. Paul office represents the role family history plays in the business.

The heads of the three partners are abstractly depicted in the mural. Out of their mouths come bubbles that contain the faces of their ancestors.

“I wanted to ask the ancestors if we could be creative,” Garrett said of commissioning the mural. “For me its perfect because it really captures the spirit of what (4RM+ULA) was about.”

Coincidentally, the art piece was finished on the anniversary of his father’s death.

” ‘Okay, we’re going to do a lot of creative work in this space; it’s official,’” Garrett remembered thinking.

Thinking globally and acting locally

Today, Garrett is one of only 15 black architects in the state of Minnesota. According to the National Association of Minority Architects, only 2 percent of licensed architects in the U.S. are black.

“For us, it’s important to be active and visible in the community (because) there are very, very, very few architects of color in the United States,” he said. “It is completely absurd and not acceptable.”

4RM+ULA strives “to let young people know this is a viable profession for people of color. This is something that is accessible, that can be done.”

One of the firm’s community projects turned out to be Garrett’s favorite, a design that has stuck with him over the years—a small, boxy, mobile shelter installed in a vacant lot in North Minneapolis, an area of the city with a predominately black population.

Called “Magic Shed,” the shelter stands out with a reflective exterior and color-changing LED lights, making it an eye-catching object that feels out of place on first glance. It can be used as a storefront for a vendor or a performance space for a musician, among other things.

It also provides a place for people to gather, activating a long disused area. The city’s black bike club meets there, and once Garrett saw a woman reading nearby, with her young child riding a tricycle around it.

Built to be temporary, the structure has been so well-loved by the community that its life has been extended more than once—Garrett calls it “the little engine that could.”

In places that don’t see a lot of public art, a little goes a long way.

“People take that kind of thing for granted in the suburbs, but we don’t take anything for granted in the inner city,” Garrett said. “People dig it, and that makes me dig it.”

This article is part of “Living for the City,” a Rewire initiative made possible by The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.

![]() This article originally appeared on Rewire.

This article originally appeared on Rewire.

Sign up for Rewire here.

© Twin Cities Public Television - 2018. All rights reserved.

Read Next