By Katie Moritz | Rewire

Martin Luther King Jr., Malcom X and Medgar Evers hold hallowed places in the United States’ civil rights history. But one man, whose name likely didn’t appear in your history book, provides a thread that binds their three stories together.

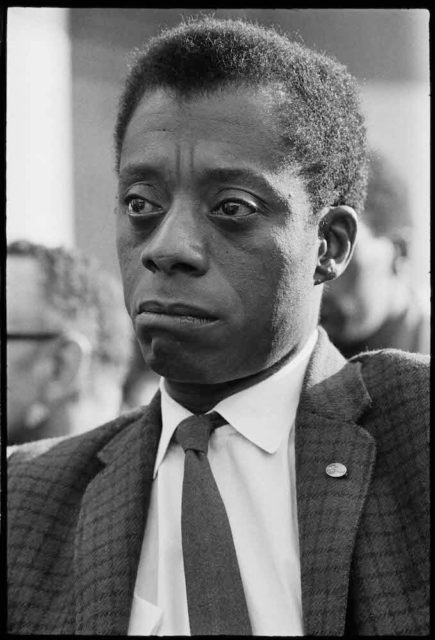

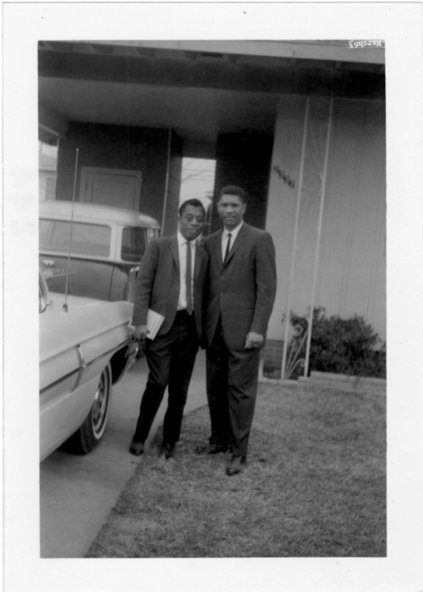

James Baldwin was a black, gay writer whose novels and essays documented and explained the civil rights movement and the realities of black life in a deeply segregated and racist society. Though his writing and speeches gripped audiences at the time, he’s far from a household name today.

A team of filmmakers wanted to change that. Decades after Baldwin’s death, a book he never finished about the murders of his friends King, X and Evers would be turned into a documentary that would grip the country, and the world.

The film, I Am Not Your Negro, directed by Raoul Peck and co-produced by Peck, his brother Hébert Peck and Rémi Grellety, was nominated for an Academy Award in 2017. Its script, narrated by Samuel L. Jackson, is adapted from Baldwin’s own writing, “Remember This House.”

“Baldwin had been really, truly effected emotionally by the death of these three friends of his,” Hébert Peck said. “He felt that, in writing this book, it will help him not only tell the story and how they all mattered and were part of the same story, but also would get him out of what he was experiencing.

“He was there during their lives as a person who was a witness to what was going on.”

Baldwin was fiercely committed to telling this story, but he died before he could finish the manuscript. The filmmakers picked up where he left off.

“In these 30 pages he was very clear about how he was going to write the book, why the book was so important and vital, telling the history of America, looking at it from a different perspective,” Hébert Peck said.

“We traditionally see American history as history from different points of view. For (Baldwin), no, this is all of the same story, and we need to tell this story, because that’s what makes us Americans.”

I Am Not Your Negro will air on PBS’s Independent Lens this month. Hébert Peck said he’s excited for it to reach new audiences in their own homes. Rewire spoke with him about the decade-long making of the documentary and Baldwin’s legacy.

Rewire: Why was James Baldwin chosen as the entry point to telling the story of race in the U.S.?

Hébert Peck: James Baldwin had been an important person initially in Raoul’s life. When Raoul was a young adult, reading James Baldwin provided him context for his experience as a young black man in a very powerful way. He read everything he could get his hands on about Baldwin and always had a Baldwin book with him. Eventually he did become a filmmaker, and it wasn’t until maybe decades later when he was an established filmmaker that he felt he wanted to tackle James Baldwin as a topic, as an important person who was one of our top writers of the 20thcentury in America.

He was interested in really creating a film that would hopefully do for an audience what Baldwin had done for him. And also he felt that Baldwin had disappeared from our society and that it was important to bring him back. The task was tougher than what I explain here—it took us 10 years to make the film.

The most important thing was to get the rights from the Baldwin estate. When we did secure the rights, we had access to everything—all of his published works, all of his unpublished materials, photographs, personal letters—which, in the industry, is kind of unprecedented. When we got the rights, number one, it was great, number two, it was a lot of pressure. You better do something good, because it was unprecedented to have that (access).

Yet at the same time Raoul was still looking for an entry to the story. He knew he didn’t want to create a typical documentary (with) experts talking about Baldwin and explaining to us what’s happening. He really wanted this to be a Baldwin experience—the story would be told from Baldwin’s perspective. He also felt strongly that the documentary or the film should use only Baldwin’s words. When you have those guidelines it puts you in a pretty tight situation.

It wasn’t until four years into the project that (Baldwin’s younger sister) Gloria Karefa-Smart handed Raoul these 30 pages of an unpublished manuscript that Baldwin had written to his literary agent about the next book he wanted to write, or the next book he felt he needed to write. Reading this material, for Raoul, it became, this is it. The task really started at that point.

Rewire: There’s a treasure trove of archival footage and photographs featured in the film. Where did all of that come from and how did you decide what to use?

HP: We had to not only look at Baldwin’s archives, but also look throughout the world at where Baldwin spoke, where he wrote, because he was really this international person, and that meant we had to look everywhere.

A lot of the footage, the civil rights footage, (people in the U.S.) are very familiar with it. Because we see it every Martin Luther King day or every Black History Month, a lot of that material is back on television or back on our screens, or back on the web. People get used to it and they don’t really pay attention to it. It becomes a symbol more than actually looking at it.

We thought, some of the stuff that we are going to use that has been used a lot—how are we going to make that fresh again? How are we going to make it possible for the viewer to pay attention to the details? The final idea was to colorize some of the footage. And in just making that switch with some of the footage, it really makes you pay attention to what you’re watching.

Although Baldwin was talking about things that happened 50 years ago, some of it resonated in the present in our current lives. How do you create that vision that the future and the past are kind of the same? So, some of the contemporary footage, some of the protest footage, some of it (is) in black and white. It’s a seamless thing that happens in the viewer’s mind and in our minds.

Rewire: There have been lots of documentaries about race. Why do you think this one became a phenomenon?

HP: I think it’s a combination of many things. Number one, I think it’s Baldwin—his ability to make us see the world with more critical eyes but in a way that it resonates with us and it makes us realize, that thing that I was thinking, it actually does make sense. Number two, I must say the way Raoul tells stories, the way he respects his subjects, the team that he had with him—from the editing team, to the researchers, to the voiceover that he had.

And also the mood in the country. You had a situation where there were things people in the black community were aware of, were sharing over the years, even over the centuries, but that up until now weren’t seen on the 10 o’ clock news or on people’s mobile devices. There was some outrage. People were having a difficult time with what they were seeing.

And I think there are so many things going on in the country at the same time. We were becoming more and more divided as a society along political lines, along racial lines, and so I think one of the things that Baldwin was able to bring to us, and I think the film, was context for what we were seeing and experiencing. There was almost this thirst for some sort of contextualizing of what we were experiencing as Americans during the past few years.

Rewire: Fifty years ago, Baldwin was skeptical that the U.S. would have a black president any time soon. We did that, and yet many problems Baldwin wrote and spoke about remain. What do you think he would say about the state of the country today?

HP: I don’t think he would be surprised at where we are now. Baldwin always talked from a point of view of love—Baldwin truly loved his country and I think he was frustrated that we continued to operate in silence as if what we call the American dream was the American dream for everyone.

He wanted to make sure we understood our history as Americans. Yeah, it’s not a pretty story, but we need to make it part of our history so we can move forward, so that we can understand who we are and we can imagine the possibilities and actually create, as he said in the film, something that has never been done before anywhere.

And so I think he would not have been surprised because he would have said we haven’t done the work we need to do; this is a logical movement toward where we are going to end up if we don’t do the work we need to do. It’s hard work but we have to do the work. Otherwise, it just gets worse each decade.

He would say yes, we have progress, the fact that we can even make a film like that, that’s a lot of progress, but we still have a long way to go. He would say it’s the responsibility of each of us to find the solution to go forward. It’s not going to come from anyone else but us.

Rewire: For people wanting to explore Baldwin’s writing, what’s your favorite book of his?

HP: “The Fire Next Time.” I think because it was my first Baldwin book, when I read it I was a young adult, it really resonated with me. After reading that I started getting my hands on everything I could get by Baldwin.

I Am Not Your Negro premieres on Independent Lens on TPT 2 January 15 at 9pm. Check back to watch the film online.

![]() This article originally appeared on Rewire. Sign up for Rewire here.

This article originally appeared on Rewire. Sign up for Rewire here.

© Twin Cities Public Television - 2018. All rights reserved.

Read Next